EXTREME E’S HYDROGEN HUBRIS MAY LEAD TO THE OFF-ROAD SERIES’ DOWNFALL

Extreme E announced its intentions to transform from a battery electric vehicle off-road series to a hydrogen-powered series in 2025 — but the incredible amount of resources required to achieve that goal has resulted in the indefinite postponement of 2024’s final three races.

At 2023’s season-ending Copper X Prix in Chile, we spoke with Extreme E and Extreme H founder Alejandro Agag about the goals of the hydrogen-powered series — and it provided a compelling look into what could be going wrong with the series now.

Alejandro Agag: “The key here is to be the only ones racing on hydrogen”

Extreme H was announced late in 2023 as a hydrogen-powered off-road series designed to replace Extreme E, where cars are powered by electric batteries — and the whole goal was to use the series as a way to develop and refine hydrogen power for both motorsport and road usage.

Hydrogen isn’t exactly a brand-new form of transportation power, but it has been admittedly difficult to implement the technology in motorsport. The 24 Hours of Le Mans has been keen to introduce a hydrogen class for several years, though ample delays have pushed the introduction of the class back by several years — perhaps until 2027.

But in speaking to media at the 2023 Copper X Prix, before the official announcement that Extreme H would replace Extreme E and that XH would join a “hydrogen research group” with both Formula 1 and the FIA, series founder Alejandro Agag repeatedly expressed his goal for the series: That it would be the first — and only — hydrogen-powered form of motorsport.

“The key here is the be the only ones that will be racing with hydrogen,” Agag said to assembled media, including PlanetF1.com.

“We want to be the first [racing with hydrogen].”

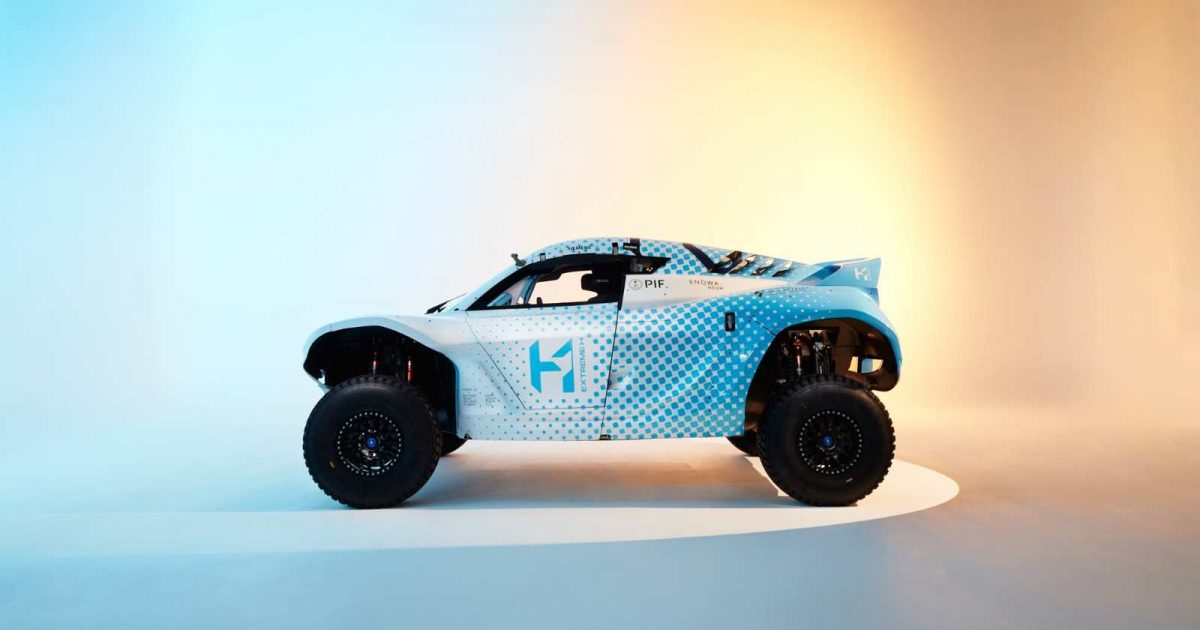

At the time, Agag made the premise sound realistic; he shared that the series had already developed a hydrogen-powered racer, and that it was able to move under its own power. Today, XH also announced that the car had passed FIA crash testing, but that it still needs to undergo resilience tests and further on-track testing.

But there’s just one problem: It has taken so many resources to design and build the XH cars that the 2023 Extreme E season — the final with battery-electric vehicles — has been placed on indefinite hold.

That means that upcoming events in both Sardinia and Phoenix, Arizona have been canceled for the time being; the series stated that it is “working closely with our teams and stakeholders to find alternative solutions to fulfill Extreme E’s final season schedule,” but there is no indication when that change would come.

The first of two Island X Prix events in Sardinia was expected to begin next weekend, on September 14-15.

Learn more about Extreme E:

👉 Formula 1 role revealed as fellow FIA series prepares for huge technological shift

👉 Lewis Hamilton ‘blown away’ as his Extreme E team pips Nico Rosberg to title

In Chile in 2023, Agag stated that he felt it would be a “challenge” to create a race series powered by hydrogen from scratch — which is why it initially made sense to maintain Extreme E’s format, albeit with different cars.

Later in the interview, Agag again stressed that he felt there is a “big, big business opportunity in hydrogen” — opportunity that would only exist “because we’re going to be the only ones [racing with hydrogen], because we’re the first one there.”

Unfortunately, it appears that being the first race series to go hydrogen has been more challenging than expected.

That is perhaps because hydrogen has not become the “alternative fuel” that many had hoped it would be.

Alejandro Agag made waves in 2013 when he announced his role in founding Formula E, which seemed an audacious ask — but not an entirely impossible one.

In 2013, Tesla had already released its Model 3, which began to change the name of the game in terms of the power used for personal transportation. However, Ford, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Fiat, Honda, Scion, and smart had all released battery-electric powered vehicles to the consumer market. The technology existed in a variety of forms, but it was up to FE to create a comprehensive racing package.

By contrast, only four hydrogen cars currently exist in the consumer market: The Honda Clarity Fuel Cell, the Hyundai Nexo SUV, the Toyota Mirai, and, most recently, the Honda CR-V e:FCEV.

Hydrogen is more commonly found in industrial and commercial uses, to power rockets, ships, and other large forms of transportation. That means finding experts who can scale their hydrogen knowledge to encompass racing cars can be a challenge.

Even more challenging is actually sourcing hydrogen. This year, Toyota Mirai owners filed a class action lawsuit in California alleging that a lack of hydrogen fuel stations meant they were unable to drive their cars. It would be somewhat simpler for a 10-car race series to cart around enough hydrogen to refuel for a race — but over 98% of hydrogen is sourced from fossil fuels and therefore creates carbon emissions.

Producing hydrogen is less efficient than charging a battery. Hydrogen is difficult to transport, store, and dispense. Hydrogen can be extremely reactive, and leaks can be difficult to spot.

All of these factors have resulted in automakers largely avoiding any experimentation with hybrid-powered vehicles — but even battery-powered EVs are becoming less popular as consumers grow disillusioned with an institutional lack of charging infrastructure.

In some ways, Agag is correct; being the first people to corner a market gives you a massive commercial boost. Formula E, for example, holds the exclusive rights to be the only all-electric open-wheel racing series until 2039; sponsors and teams that want to engage in racing, then, have little choice but to opt for FE.

But there was, at least, consumer interest in electric vehicles when Formula E debuted — meaning that sponsors and automakers could join the series in order to learn about the kinds of technologies they wanted to implement in more vehicles in the future.

Honda is the sole automaker to introduce a hydrogen-powered vehicle in the last five years. Why? Because most automakers have determined that hydrogen-powered vehicles will be more challenging to develop than they’re worth.

In Chile, Agag admitted that he was “optimistic” about being able to race hydrogen-powered cars in Extreme H by February of 2025, but that he “wasn’t optimistic three months ago.”

He noted that the XH designers had run into concerns with fuel cell supply and production, with testing, with software, and with generally making the hydrogen fuel cell technology work. But in Chile, Agag told us the car was up and running, and that it had achieved almost all of its Key Performance Indicators.

There is, however, a large gap between building a functional prototype and developing multiple race-ready machines that have been tested for safety, resilience, and reliability. It appears that the task has proven far more difficult than expected — and the final season of Extreme E has suffered for it.

Read next: Exclusive: How a hydrogen-powered Championship could impact F1’s future

2024-09-06T19:19:45Z dg43tfdfdgfd